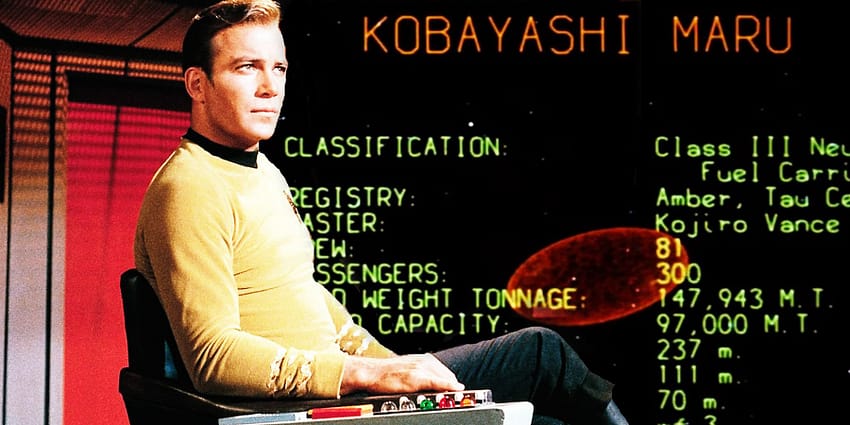

Those familiar with Star Trek will know the Kobayashi Maru simulation. It’s a test given to prospective starship captains to test their reactions in a no win scenario. In that test, no matter what they do, the ship and crew are all destroyed. But unlike Captain Kirk, who passed the test and saved everyone by secretly reprogramming the simulation so there was a way to beat it, Apple finds itself in a no win situation.

In 2021, Apple announced that it would use a tool to detect child sexual abuse material (CSAM) in photo libraries. The tool would not scan images directly but would use hashes of known CSAM. This would not be tool that scanned the actual content of every image. It would see if the hash of an image matched images in a database of images by using the hash — which is effectively a digital fingerprint.

The method would not be used to scan the content of a photo — only that its digital fingerprint matched the fingerprint of an image in a database. To take the fingerprint analogy further, it could not know someone’s identity unless those fingerprints were in a database.

The feature required people to opt in via settings in family iCloud accounts. Its purpose was to enable parents to block the sending, receiving and storage of CSAM images by their children. Apple said the goal was “to stop child exploitation before it happens or becomes entrenched and reduce the creation of new CSAM.” (Source: Wired)

Apple announced that it was going to release the feature but changed its mind after widespread criticism from privacy advocates.

Now Apple is being sued by victims of childhood sexual abuse. A filing made on behalf of survivors says the class action is “on behalf of thousands of survivors of child sexual abuse for [Apple] knowingly allowing the storage of images and videos documenting their abuse on iCloud and the company’s defectively designed products. The lawsuit alleges that Apple has known about this content for years, but has refused to act to detect or remove it, despite developing advanced technology to do so.” (Source: Forbes)

In other words, if Apple enables image flagging for CSAM it is pilloried by privacy advocates. But if it doesn’t, it can be sued by victims of abuse who might have been protected by Apple’s efforts.

Walking the privacy tightrope

The tightrope between protecting privacy, meeting the demands of law enforcement agencies and preventing exploitation of the vulnerable is razor thin.

Quite frankly, Apple can’t win. If it scans, detects and identifies CSAM using hashes it is accused of potentially breaching the privacy of about a quarter of the world’s population. On the other hand, not identifying this material can result in a lifetime of misery for the victims of these hideous crimes.

And all of this is playing put with Apple’s stance on encryption playing out against law enforcement agencies that want to have access to encrypted messages so they can catch criminals that use encrypted systems to share information about crimes.

There are no simple answers to this. I think Apple should be able to scan, detect and identify CSAM using hashes. But it needs to do a much better job of communicating how this works and why the risk to individual privacy is minimised. This was something it did poorly in 2021.

With encrypted messaging, law enforcement agencies will need to get smarter. Weakening the privacy of billions of people across the world cannot be the only way to solve this problem. Rather than dictating what Apple and other tech companies should do, it needs to take a more cooperative position. And they need to get smarter about technology.

Anthony is the founder of Australian Apple News. He is a long-time Apple user and former editor of Australian Macworld. He has contributed to many technology magazines and newspapers as well as appearing regularly on radio and occasionally on TV.